ISLAND ARC

Oceanic volcanoes collide: Island arcs rise, forming fiery chains along tectonic plate boundaries.

ISLAND ARC

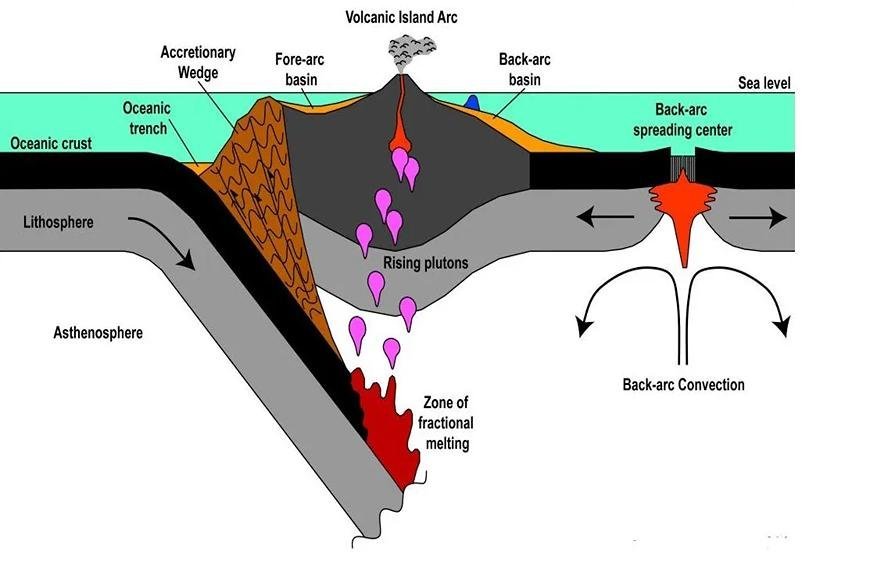

- When oceanic lithosphere is pushed under oceanic or continental lithosphere, island arc systems are formed.

- As a result, they are common along the edges of seas that are getting smaller, like the Pacific, where most island arcs are found.

- The Lesser Antilles (Caribbean) and Scotia arcs are located at the eastern edges of small marine plates in the western Atlantic that are moving away from the main westward trend.

- Island arcs are known to be tectonically busy belts with a lot of seismic activity that contain a chain or arc of active volcanoes.

- Even back in the 1800s, W. J. Sollas pointed out that the arc-shaped Aleutians/Alaskan Peninsula, the East Indies (now Indonesia), and several mountain chains were all similar to a set of large circles.

- Meanwhile, C. Lapworth talked about the "Volcanic Girdle of the Pacific" (also known as the Pacific "Ring of Fire") as a continuous "septum" separating "plates" with different histories and thicknesses.

- The deepest parts of the seas, called deep-sea trenches, were on the side of these curves that faced the ocean.

- As scientists studied the "ring of fire," they found that there was a line around the Pacific that separated andesitic rocks (named after their type area in the Andes) from basalt rocks. It was known as the "andesite line.".

- Before geological data were collected, not much could be done to find out where island arcs came from.

- The idea of a simple, steeply dipping thrust plane going from near the trench to a depth of up to 700 km wasn't clearly established until 1949, when H. Benioff showed that earthquake epicentres got deeper as you went from the ocean side of the trench to the volcanic arc.

- In the 1950s, a lot of geological data was collected in the Pacific, off the coast of Indonesia, and in the Caribbean.

- This data suggests that big slabs might be dragged down under island arcs along subduction zones, which are also called Benioff zones.

- After that, there wasn't another big step forward until 1968. In the 1960s, the idea of ocean floor spreading meant that new lithospheres were being made all the time.

- No matter what, a certain amount of lithosphere had to be lost, and it looked like this would happen most likely at the subduction zones.

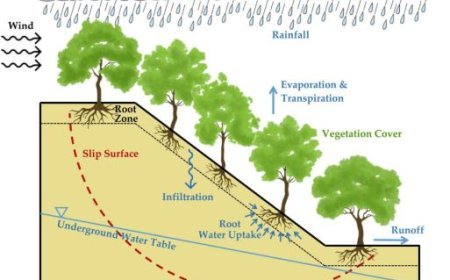

- When the oceanic lithosphere rock goes down, it partially melts at a depth of 150–200 km. This creates magmas that rise and are pushed out of volcanoes 150–200 km from the trench's line.

- People often use "island arc" instead of "volcanic arc," but the two words are not quite the same. Volcanic arcs are all belts of active volcanoes that are above a subduction zone.

- They can be islands in the middle of the seas or countries, like the west coasts of Central and South America.

- Only true island loops, like those in the Caribbean, have a body of water separating them from the land. Because of this, there are a range of island-arc types:

- Some are truly intra-ocean, meaning they are completely in the ocean. In the Pacific, these include the Marianas, the New Hebrides, Solomon, and Tonga. In the Atlantic, these include the Antilles and the Scotia arcs.

- Others are divided from the main continents by small oceans or lakes on the edges of continents, and their crust is a mix of continental and marine. These include the Andaman Islands, Banda, Japan, Kuril, and Sulawesi.

- On the other end of the range are arcs that were formed against continental rock. These include the Burmese and Sumatra/Java parts of the Burmese Andaman-Indonesian arc.

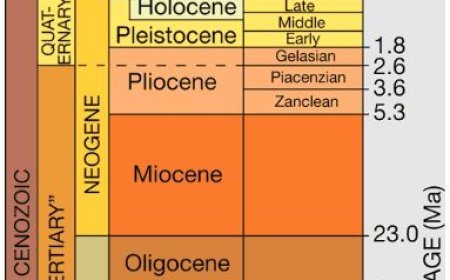

- Finally, there is the Andean chain. This one's volcanic belt is completely inside the continent, so it's not an island arc. The age changes too. Some are less than 10 years old, which is less than 106 years. Some are much older, going back to at least the Tertiary or Cretaceous periods.

- There are several traits of tectonic zones that go from the gap at the ocean-facing end to the marginal or back-arc basin on the mainland side. The open island arc is one of them.

Fore-arc region

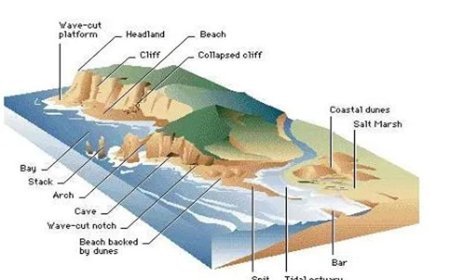

- From the side of the system that faces the ocean, there is a 500-metre-high bump about 120 to 150 km from the trench.

- It is made up of the trench, the subduction complex (also called the "first arc" or accretionary wedge or prism), and the fore-arc basin.

- The leading edge of the plate above the sinking slab scraped thrust fragments of trench fill sediments and possibly even oceanic crust off of it to form the subduction complex.

- A lot of the time, back-thrusting happens where the accretionary wedge meets the fore-arc basin.

- The fore-arc basin is a calm area with flat-lying sediments that lies between the fore-arc ridge and the island arc.

- The "second arc," or island arc, is made up of a rock arc on the outside and a volcanic arc on the inside.

Sedimentary arc

- Coralline and volcaniclastic sediments make up the sedimentary arc, which is overlain by volcanic rocks that are older than the rocks in the arc.

- This volcano base could be the first place where magma erupted when the relatively cool oceanic plate started to fall.

- The volcanic arc now demonstrates how the extrusive igneous activity moved backwards to where it was in a steady state as the "cold" plate moved deeper into the asthenosphere.

- Behind the island arc, the back-arc ridge, or "third arc," and the leftover arc form a ring around a small sea called the back-arc basin.

- In general, these fringe seas are 200–600 km wide. On the side of an island curve that faces the land, there may have been up to three generations of fringe seas.

Subduction zone

- We can find a subduction zone by looking for seismic centers. These are places where a lot of seismic activity is happening on top of the piece of lithosphere that is sinking.

- The earthquakes establish the "seismic plane" of the subduction zone, which can be up to 30 km wide.

- Most subduction zones dip at angles between 30° and 70°, but some subduction zones dip more strongly as they get deeper.

- The dip of the slab is directly tied to the speed of convergence at the trench and depends on how long it's been since subduction began. It tends to sink quietly because the slab of lithosphere that is going down is heavier than the thin asthenosphere below.

- The older the lithosphere, the greater the dip.

Trench

- The deepest parts of ocean areas are the trenches, which can be anywhere from 7,000 m to almost 11,000 m deep. Both the Mariana and Tonga pits are very deep.

- Most of the deep-sea tunnels in the Pacific are made of normal basaltic oceanic rock and are covered with thin layers of sediment and ash from the sea floor.

- It is easy for this thin layer of sand to move under the plate that is on top of it.

- Ocean pits form when the marine lithosphere is pushed under. They can be found on the ocean side of both island arcs and mountain ranges of the Andes type.

- They are the biggest depressions on the earth's surface and stand out for how deep and continuous they are. The Peru-Chile trench is about 4,500 km long and 2–4 km below the ocean floor. This means that the bottom of the trench is 7–8 km below sea level.

- In general, trenches are 50–100 km wide. They have an uneven V-shaped cross-section, with the higher side facing the ocean rock that is pushing it down.

- The amount of silt fill changes from almost nothing (like in Tonga-Kermadec) to almost full (like in the Lesser Antilles Trenches).

Volcanic arc

- Wide layers of volcanic rock that are several kilometres thick surround oceanic volcanic arcs.

- The apron is mostly made up of pieces of pyroclastic material.

- Many earthquakes happen and sediment moves quickly because the underwater slopes of arc-related volcanoes are high. This is because of slumping, sliding, and turbidity currents.

- A look at both current (like the Lesser Antilles and the New Hebrides) and old island arc systems has shown some of the following:

- The spreading of materials around an arc isn't always even. This is because of the way the winds blow, the different slopes of the arc, and the currents in the ocean (for example, in the Lesser Antilles, winds blow most of the ash into the Atlantic).

- The island or individual volcanoes can move, usually towards the ocean, towards the trench, or along the arc.

- As the volcano rises into shallow water and erupts, it creates stronger explosions that send ash farther away from the volcano.

- Sedimentary processes are always forming layers of volcanic ash. The top layer is made up of pillow breccias, debris-avalanche, and lahar (mudflow) deposits. The middle layer is made up of debris-flow deposits. And finally, the bottom layer is made up of fallout ashes and turbidites.

- As island arcs grow, get bigger, and mature, like in Japan and New Zealand's North Island, sands and plants from the land fill the spaces between the islands, and ponds and lakes form, mostly inside the calderas of volcanoes.

Back-arc basin

- Back-arc basins, also called marginal seas, are small ocean basins that are found on the inner, curved sides of island arcs.

- A back-arc ridge, also known as a leftover arc, surrounds them on the side that is opposite the arc.

- Most of the time, they live in the Western Pacific, but you can also find them in the Atlantic, behind the Caribbean and Scotia arcs.

- It is possible for tensional tectonics to cause marginal basins.

- This happens when an existing island arc is split in half along its length, creating the basin.

- One interesting thing about the western Pacific Ocean is the huge area that is made up of a complicated system of basins that lie behind the volcanic arcs and touch the land.

- It has been controversial about these fringe basins ever since it was found that their crusts move at speeds closer to those of oceanic crust, even though their thickness is usually close to that of continental crust. It is now known that most marginal basins are made up of old ocean bottoms stuck behind an island arc.

- These can be found in the western Pacific, the Andaman Sea, behind the Burmese-Indonesian volcanic arc, and behind the Antillean and Scotia arcs.

- They range in age from very young back-arc basins that formed within the oceanic rock not long ago (intra-oceanic back-arc basins) to older basins next to continents, like the Japan Sea, which are not active at the moment (continental back-arc basins).

Benioff zone

- Volcanic activity is very strong in island arc systems. On a plane that deviates from the marine plate by an average of 45°, many things take place.

- The plane is called the Benioff (or Benioff-Wadati) zone after the person or people who found it.

- Earthquakes happen on it from the ditch at the surface all the way down to a depth of about 680 km.

- At these depths, earthquakes happen because the strong, falling slab of the lithosphere is deforming inside. This means that most of the events happen about 30–40 km below the top of the slab.

- Having earthquakes that happen more than 70 km below the surface

- Along the edges of seas, there are ridges that look like mid-ocean ridges. The East Pacific Rise is one example. Aside from the volcanic lines that form subduction zones, there are other peaks that spread out. Most of the time, these are called back-arc spreading centres.

- The peaks rise above the ocean floor because they are made of rock that is hotter and less thick than the older, colder plate.

- As the plates separate, hot mantle material rises from below the ridges to fill the empty space. As it rises, it loses some of its compressive force and partially melts.

- At the top of the ridge, the lithosphere may only be made up of marine crust, which is made up of basaltic rocks.

- The peridotitic (olivine-rich) mantle part grows quickly as it moves away from the spreading centre and cools and shrinks. The water depth goes up because of the restriction.

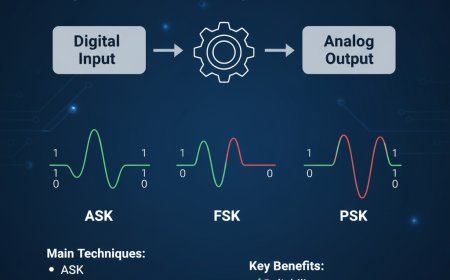

IMAGE SOURCE (THUMBNAIL)

What's Your Reaction?